This piece, by Wil Wheaton, originally appeared on the End User blog on 3/27/09.

"2009 is the year that print on demand goes mainstream." – Warren Ellis

We are living in an incredible time, both as consumers and creators. As consumers, whatever entertainment we want, whether it’s television, music, movies, games or books, is easier and faster to get than ever before. As creators, the barriers between us and our audience are falling faster and more easily than ever before, the time between creation and release is shrinking, and thanks to the Internet we can reach more people with less effort than we could as recently as a decade ago.

Earlier this week, I came across a post in my blog archives from September of 2002 where I said:

Remember how so many readers have been telling me to write a book? Well, I listened. Watch this space for details on how you can get it in about a week or so, maybe two.

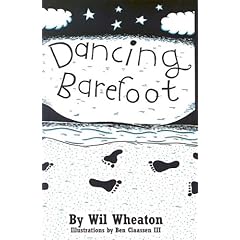

I was talking about my book Dancing Barefoot, which was created from material I cut out of Just A Geek. I looked at that post and felt a little nostalgic, because that’s where my journey as a published writer and champion of indie publishing began.

I was talking about my book Dancing Barefoot, which was created from material I cut out of Just A Geek. I looked at that post and felt a little nostalgic, because that’s where my journey as a published writer and champion of indie publishing began.

In 2002, I was just another struggling actor and fledgling blogger. I figured that, since I was having such a hard time getting work as an actor – where I had a huge resume and a lifetime of experience – it would be nearly-impossible to sell my books to a publisher. I did some research, figured out that I was able to reach a few hundred thousand people with my blog, and decided to reject the "traditional" publishing route in favor of self-publishing.

I needed an education in self-publishing, and read two books that made all the difference: The Complete Guide to Self-Publishing and The Self-Publishing Manual. They were both filled with great advice, like the importance of hiring and respecting an experienced editor, a good designer, and putting together an intelligent marketing plan. I’m not sure what the current versions of the books say, but in 2002, they both warned authors away from using print on demand, largely because the per-unit costs were unreasonably high, and when you held a POD book in your hands, it really felt like you were holding a POD book in your hands.

My, my, my, how the times have changed. The prejudice against POD persists, but that tactile difference in quality has vanished, and after a couple of my friends used print on demand from Lulu to release their books, I decided to give it a try myself. I wrote in my blog:

If this works the way I think it will, it’s going to be super awesome for all of us as I release books in the future: You don’t have to worry about me screwing up your order, I don’t have to invest in a thousand books at a time, you get your book in a few days instead of a few weeks because I’m not shipping it myself, and I can spend more time creating new stories while remaining independent. Best of all, I’ll have the time to write and release more than one or two books a year.

Read the rest of the post on the End User blog.